Hist 387_2 The first written records of Chinese history

The Shang (ca.

1766-1045 BCE)

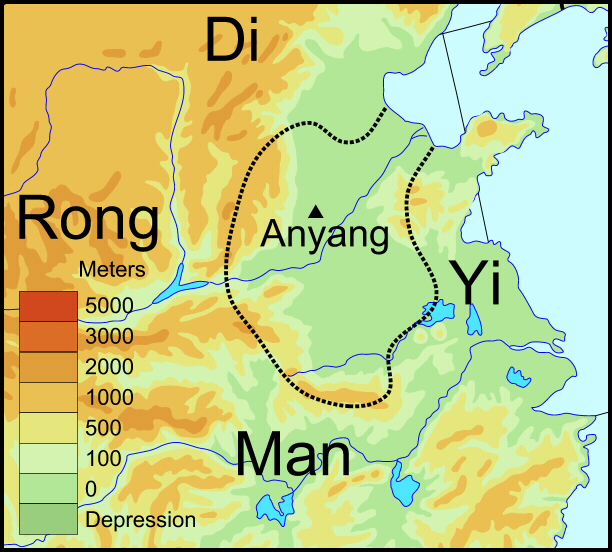

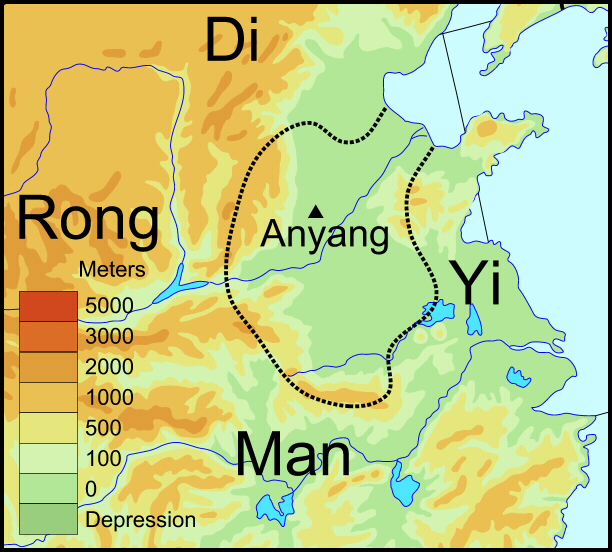

Map of Shang Dynasty territory with the capital Anyang

Records written by the Shang and historical records reporting about the Shang

The first written records of the Shang (ca. 1766-1045 BCE) were divinatory inscriptions in tortoise plastrons or scapula bones found in an archive at the site of the ancient Shang capital of Anyang in Henan province. Topics addressed in this communication with the gods of nature and the spirits of the ancestors were wide ranging: They included weather prognostications and questions about warfare, health, remedies against sickness, correct behavior in ritual sacrifices, results of childbirth, as well as neighboring states etc. The Chinese writing system developed out of these characters used in divination of which ca. 3000 have been identified, and ca. 1500 can be translated into modern Chinese. The characters can be identified without knowing the pronunciation which makes this ideographic language an ideal means of communication between people speaking different dialects (or even different languages; both languages, Korean and Japanese, contain a certain amount of Chinese characters even today; in former times, learned scholars from all three countries could communicate with each other in writing: Chinese became the lingua franca of Asia).

Distribution of the Chinese script

Distribution of the Chinese script

The excavations at Anyang not only revealed the archive but also brought tombs of Shang kings and a queen to daylight. Lady Hao, consort of King Wu, ruled over her own territory and commanded her own army. Her richly equipped tomb contained bronze vessels, hairpins, jade and ivory objects, weapons, and money in the form of cowry shells. She was accompanied by 16 men, women, and children to serve her in the afterlife. Prisoners of war could be killed to act as slave-servants in the afterlife.

Tomb of Lady Fu Hao

Bronze ding from Lady Fu Hao's tomb

Bronze zun from Lady Fu Hao's tomb

Ivory

cup of Lady Fu Hao

Ivory

cup of Lady Fu Hao

Ceremonial axe from Lady Fu Hao's tomb

Jade elephant from Lady Fu Hao's tomb

Jade figurine from Lady Fu Hao's tomb

Jade animal from Lady Fu Hao's tomb

Bronzes were used as sacrificial and storage vessels, but also as documents of enfeoffment. Bronze could be finely decorated - mostly with abstract geometric patterns or animal designs, even with inscriptions memoralizing certain important events or names. Bronze is an alloy of copper, tin, and lead, a composition that facilitates decoration and when polished, shines brightly.

The vessels found in Anyang reveal the importance of food in ritual in ancient China. Different vessels were used for cooked meat, heated alcoholic beverages, and cooked or steamed grain (mostly millet at the time). The ancestors were believed to consume the 'qi' or spiritual quality of the food offered to them in the sacrifices.

The inscriptions reveal a hierarchy in the spiritual world headed by the supreme deity, Shangdi. Nature embodies spirits: they can live in mountains, streams, even trees, and dominate life or existence within the earth. The Shang kings and their clan were seen as mediators between the spiritual world and man.

The Records of the Grand Historian

(Shiji), written by Sima Qian (ca. 149-90 BCE) in the Han Dynasty,

reports about the Shang:

We learn that the Shang moved their capital several times and the capital resembled

more a fortified exclusive camp (?) with buildings for rituals and banquets,

workshops for the artisans, storages for grains and food, stables for horses,

etc. than a capital with buildings for urban administration. From there the

kings went on hunting expeditions and had the kand cleared for crop cultivation.

Contemporaries of the Shang

The Sanxingdui-site in Sichuan

Close to Chengdu, in Sichuan Province, an archaeological excavation conducted in 1986 helped to rescue objects from two sacrificial pits created by people of the Bronze age who were contemporaries of the Shang, but did not leave any written records. The pits contained elephant tusks and small as well as huge bronze masks, many of them damaged (supposedly on purpose) before buried in the pit.

Map

of Sichuan with the location of the Sanxingdui site

Map

of Sichuan with the location of the Sanxingdui site

This

mask was originally mounted on a (wooden?) pole

This

mask was originally mounted on a (wooden?) pole

Ceremonial masks from the Sanxingdui excavation

Ceremonial masks from the Sanxingdui excavation

The Tarim Mummies

The desert of the northwest provided more material on contemporaries of the Shang in Anyang. In modern Xinjiang more than 100 corpses of people who lived between 2000 and 500 BCE have been preserved. The majority of these corpses have caucasic features like large noses, fair hair and complexion, some of them are unusually tall (6 feet). The textiles they wear which were woven on looms different from those used by the Shang, seem to indicate that they travelled to the Chinese borderland; some historians speculate that they may have introduced the wagon to China.

The Zhou (1045-256 BCE)

Map of Zhou Dynasty territory

Among the non-Shang populations mentioned in the oracle bones are the Qiang (who were found as sacrificed prisoners-of-war in Shang tombs) and the Zhou, who came to be the successors of the Shang.

The Zhou dynasty (1045-256 BCE) did not only leave written sources in the form of bronze inscriptions but was later also described in written sources, among them the classical texts of the Book of Songs (Shijing) and the Book of Changes (Yijing). Sima Qian reports about the concept of the 'Mandate of Heaven', used by the Zhou to describe the consent of Heaven (complementing the more personified supreme deity Shangdi of the Shang) to the actions of a ruler. This consent was the basis of his power; having lost the mandate to rule, power could be transferred to a successor. Natural desasters were thought to indicate heavenly dissent which resulted in a change of rule.